In Brief

What is New?

A more youthful appearance is a surprisingly reliable indicator of also being younger “under the hood”.

Why This Matters

Since staying younger is a consequence of lifestyle choices, the benefit of “looking younger” might be a powerful incentive to adjust one’s lifestyle choices.

How To Get There?

With a reliable, evidence-based, and lay-capable biological clock that gives real-time feedback on lifestyle choices’ effects on the rate of biological aging.

Looking Younger As A Measure Of Aging and Health

You have probably already discovered that some people look a lot younger, and others a lot older, than they really are.

It is not so obvious among the 20-somethings. But when most of your friends and acquaintances were born before the internet, you’ll have realized by now that the biological clock runs faster for some and slower for others. Aging is not just a matter of time, but also of biology.

Ignoring, for a moment, Hollywood’s obsession with youthful looks, looking younger than one’s age is far more than a matter of vanity.

It is a reflection of one’s physical and cognitive health, too. In a study of 954 38-year-olds, those who looked older to independent observers, showed measurable deficits in physical and cognitive function compared to their same-age peers [1].

That suggests that looking younger than what one’s passport says may be a legitimate medical intervention target.

For that to be true, two conditions must be met. First, it must be possible to measure biological age, and second, such a measure must demonstrate responsiveness to intervention.

For obvious reasons, Botox injections, hair transplants, and face lifts do not count as interventions.

How To Measure Biological Age?

With respect to measuring biological age, we already have several biological clocks available. Most of them are based on DNA methylation. That is the attachment of methyl molecules to the DNA chain.

Think of them as “do not disturb” signs, which prevent genes from being expressed.

Altering gene expression will alter the function of cells. In the case of DNA methylation, cell function becomes less efficient and more prone to disease.

Typically, the degree of methylation is a one-way street throughout the aging process. That’s why DNA methylation has all the trimmings of a biological clock.

Can Lifestyle Change also Change Biological Age?

Can we slow down or reverse this clock? And does this affect health outcomes, too?

A recently published study in humans suggests a “yes” to both [2]. But before you get all excited, the studied intervention is not a very popular one. Participants, all of whom were of normal weight, had to restrict their energy intake to 75% of normal for 2 years.

In the end, their rate of aging had slowed down by 2–3%.

That doesn’t sound like much. It is certainly a lot less than the life-extension that we see in calorie restricted rodents (which goes to show that humans are not just large, two-legged rats, even if some contemporaries might give us pause).

To me, this study is remarkable for a reason not discussed in excited press reports.

The researchers had compared the performance of three different biological aging clocks. Two failed to register any change. The third was different from the others as it included functional biomarkers, not only those of DNA methylation.

Maintenance Of Function Is The Key Objective

“Function” being the key word. Function is, in my eyes, the acid test for the benefits of interventions to slow down aging.

Because the functional impairments that we associate with older age, from dementia to heart failure to frailty, are what make life so burdensome for, let’s face it, most older people.

Another recently published study gives us hope in this respect. A lot more hope, in fact.

It demonstrated how an exercise intervention quite dramatically shifts the DNA expression profile towards a younger state, and how muscle disuse does the opposite [3].

It is muscle that gets Grandpa out of the chair, dance with Grandma, or swing the tennis racket. It is exercise that trains muscles. Calorie restriction does not.

That’s why I am a fan of exercise as the primary mode of slowing down the biological clock. And that’s why I am a fan of functional biomarkers as the benchmark for measuring the effects of whatever we do to slow down aging.

My Team’s Biological Clock

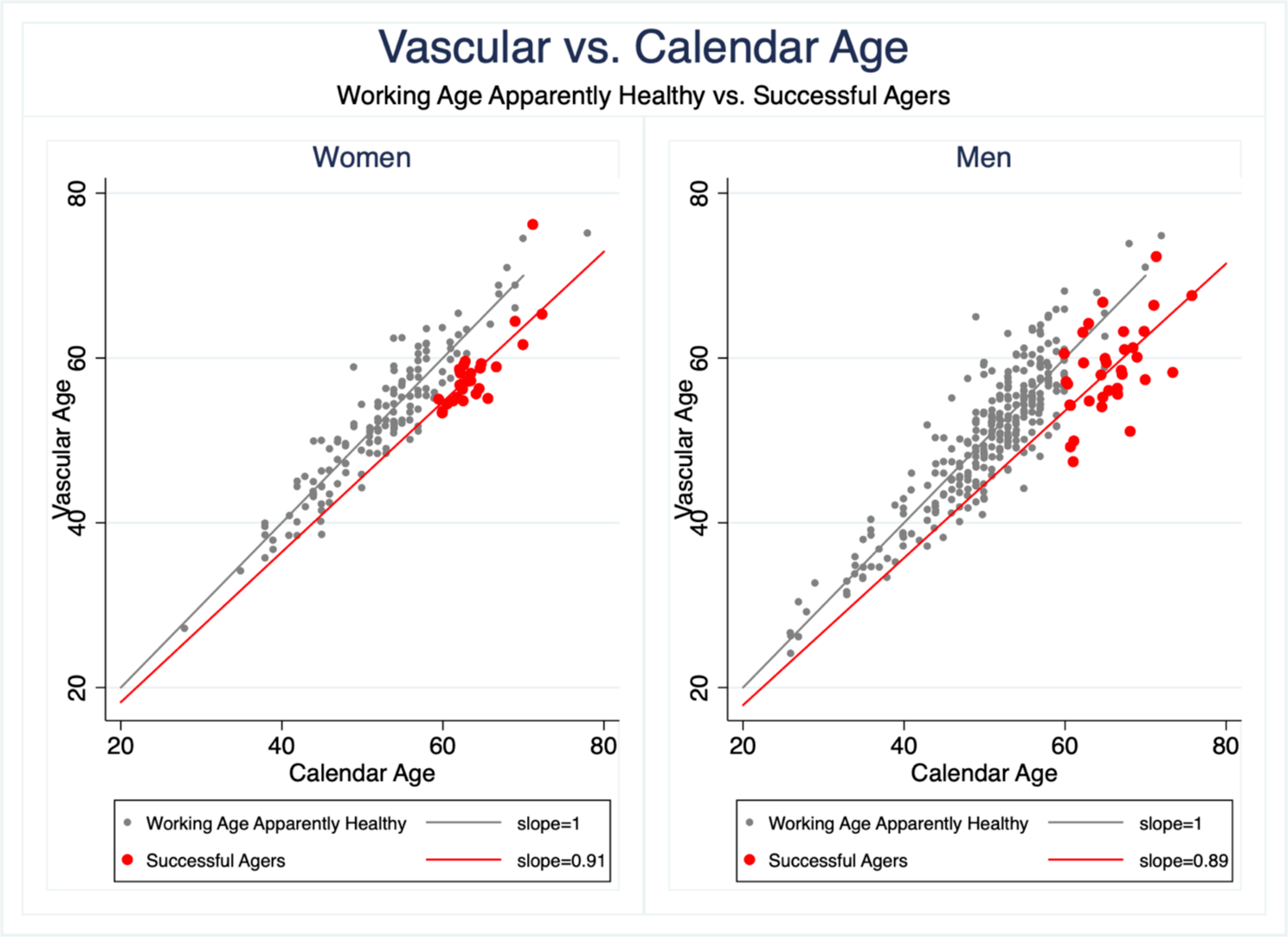

To serve this purpose, my team and I have developed an easy-to-measure biological clock based purely on arterial function parameters (remember the old adage: man is as old as his arteries).

We compared the rate of aging of healthy, disease-free, and medication-naïve 65+ year-olds with the normal population. And we discovered that the rate of aging can be slowed down by 10–15% or even more. That is, one ages at 10–11 months per year instead of the regular 12 (or more for those who age faster).

All of those slow-agers also exercised regularly and were physically fit. Most of them didn’t look their age. That doesn’t make looking younger a legitimate medical intervention target, but it certainly answers the question:

Can You Become A Slow Ager?

Yes, you can. Provided you have what it takes to make that happen.

And not to forget: The earlier one starts, the greater the benefit.

PS: If you want to know more about our work, visit our website, and follow me on LinkedIn and/or my company, adiphea.

Hashtags

#slowaging

#biologicalclock

#exercisebenefits

#arterialhealth

References

[1] Belsky DW, Caspi A, Houts R, Cohen HJ, Corcoran DL, Danese A, et al. Quantification of biological aging in young adults. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2015;112:E4104–E4110. doi:10.1073/pnas.1506264112.

[2] Waziry R, Ryan CP, Corcoran DL, Huffman KM, Kobor MS, Kothari M, et al. Effect of long-term caloric restriction on DNA methylation measures of biological aging in healthy adults from the CALERIE trial. Nat Aging 2023;3. doi:10.1038/s43587–022–00357-y.

[3] Voisin S, Seale K, Jacques M, Landen S, Harvey NR, Haupt LM, et al. Exercise is associated with younger methylome and transcriptome profiles in human skeletal muscle. Aging Cell 2023:1–15. doi:10.1111/acel.13859.